An extended and revamped pavilion and new playing surfaces were reopened by former England cricketer and Westminster coach at special ceremony

The first weekend of the new school year saw sporting action on the pitches of Vincent Square for the first time in more than a year.

Football, netball and tennis matches between School teams and Old Westminsters on Saturday 2 September were followed by a special reopening of the square by Roland Butcher, England’s first black Test and One Day cricket player, and also a coach at the school throughout the 1990s.

The event marked a year in which the Square was transformed. The School Pavilion, built in 1888, has been refurbished and extended with two new wings designed by the surveyor to Westminster Abbey, Ptolemy Dean. At the same time, all ten acres of the playing fields were renewed with new drainage and irrigation, meaning sport will be playable all year round, whatever the weather.

Dr Gary Savage, Head Master, said: “It is a real joy to see Fields teeming with life again, following a year bereft of home fixtures. Our teams have retained their spirit throughout this period of enforced absence, but to play on Vincent Square again will, I know, be very welcome.

We are extremely grateful to all staff and donors who have made the refurbishment of the pavilion and extensive work to the playing surface possible through their hard work and generosity. The project has not been without its challenges, of course; and so we are very proud that all of these have been overcome and we now have a spectacular new facility, for use by pupils from both Westminster School and Westminster Under School throughout the year, in good weather and in bad.”

Fields — A Short History

From duck shooting and ice skating to football and cricket, the playing field we now know as Vincent Square has long held physical challenges and sporting distractions for the pupils of Westminster.

Today’s enclosed area of grass is the last ten acres of the former Tothill Fields, or Tuttle Fields, a vast swathe of open and marshy land between Westminster, and Chelsea. This was a place of tournaments, fighting, and the settling of wagers in medieval times, the site of Henry III’s annual 15-day Tothill Fair – funds from which he would use to finance the building of his great Abbey, the burial of plague dead, and a place where troops would conduct drill and musket practice during the Civil War.

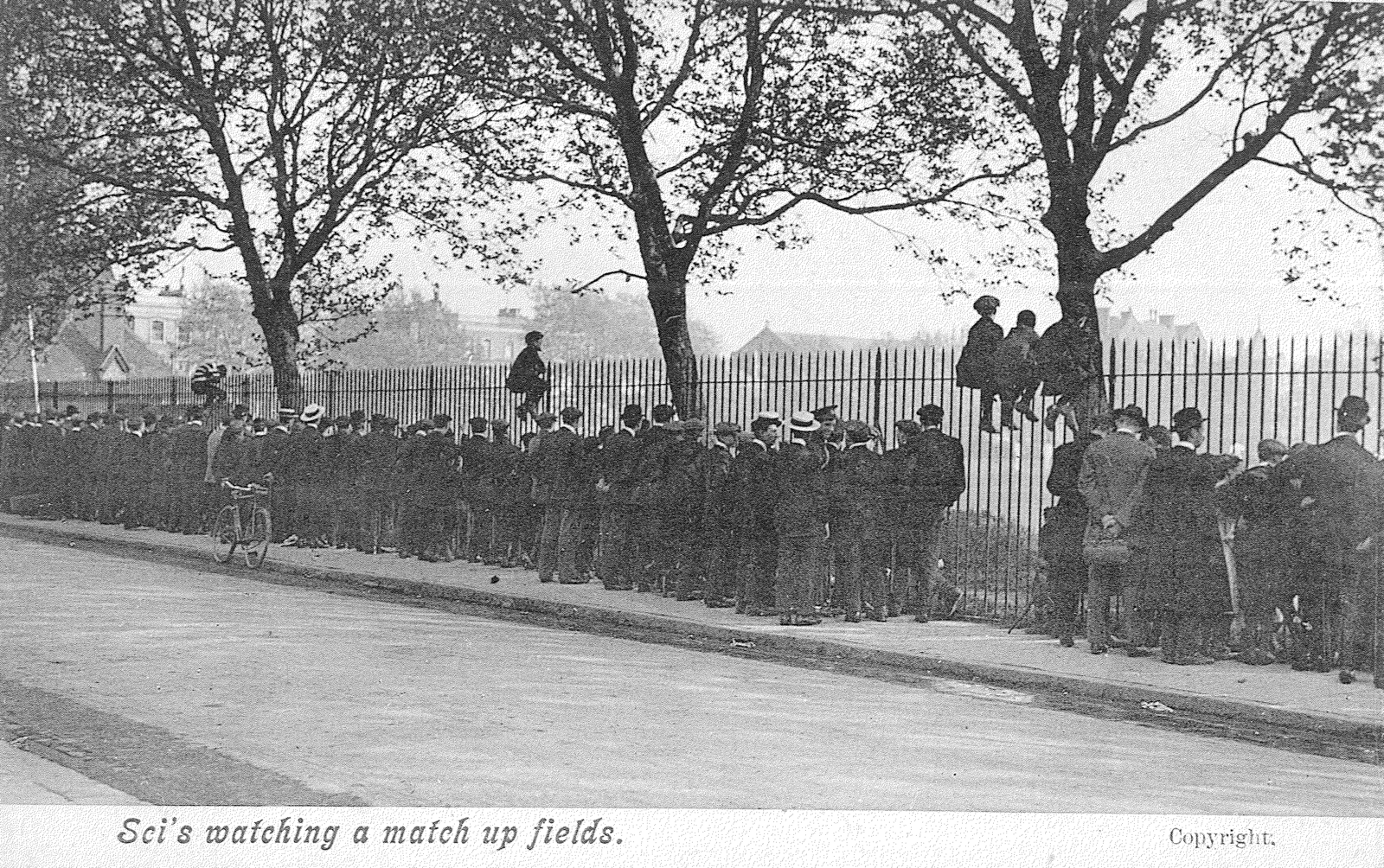

The vastness and proximity of the fields was a lure for Westminster boys from the early days of the school, with many activities on offer. Some are long past – duck shooting, ice skating, ditch leaping, donkey racing – and those that remain, including some of the very earliest mentions of cricket on record. Westminster was an early adopter of cricket. Competitive matches were played on the fields in the mid-1700s, long before the laws of the game were codified, the chief event of the season being the Scholars vs Town Boys match.

It was in the early 1800s that the square we know today took shape. Much of Tothill Fields was being lost to housing, a situation the Dean of Westminster and former Head Master, William Vincent, viewed with alarm. Despite ownership of the land being a long-running dispute between the Abbey and two local parishes, Dean Vincent sought to mark off an area of land for the exclusive use of the School. So in 1810 he paid £3 for a furrow to be ploughed around this ten acres, later fully enclosing it with a fence. The Public Schools Act of 1868 confirmed the land as the School’s. Tothill Fields had gone and in its place was Vincent Square.

Although it is recorded that Westminster and Charterhouse played at cricket in 1794, and Eton in 1796, it is in the 1800s that we saw an explosion of sporting competition and the introduction of regular fixtures, including those with MCC and the Lords and Commons, as well as against many other schools.

The first recorded football on the Square is in 1854, but it is likely the game was played before that.

In the mid-1800s football, still a young game, proved a tricky one to play as rules would vary between schools. The handling of the ball and drop kicks were still common.

This state of affairs pleased no one. In 1863, a letter in the Times from Etonians said: ‘The display is below mediocrity – neither of the sides can practice any of their favourite dodges without infringing the rules of the other.’

The Westminster Charterhouse fixture, first contested in 1863, has a claim to be the longest continuous football fixture in the world. As on the water between Westminster and Eton, both Westminster and Charterhouse competed for the right to wear much-prized pink. One Charterhouse coach, much later remarked: ‘Was that really a prize worth winning?’.

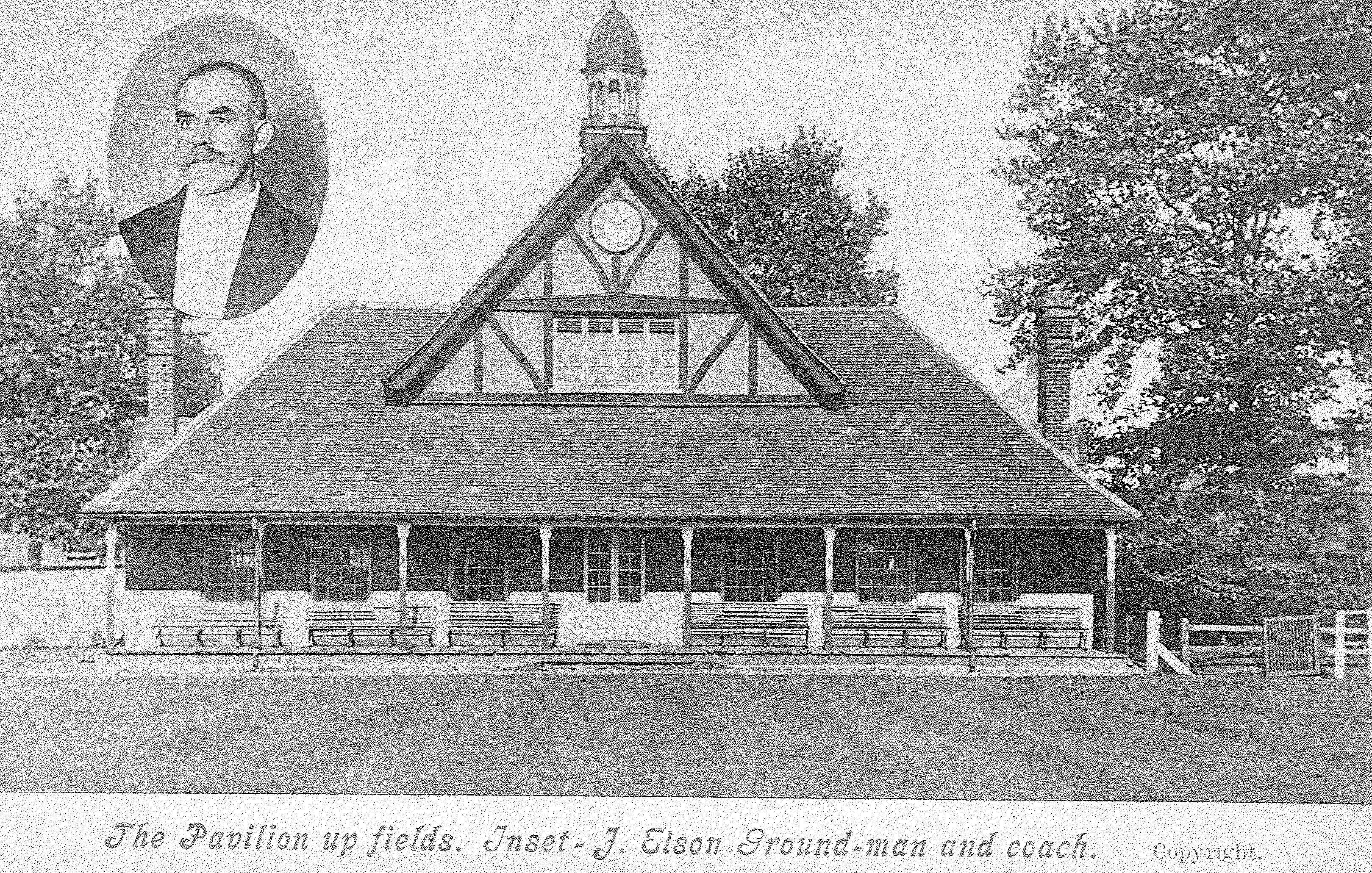

The Pavilion we see today dates from 1888, designed by Scottish architect Richard Creed FRIBA, and built by subscription with funds from numerous sources: £225 from the Elizabethan Club, £200 from the Governing body, £300 by the Masters’ Fund, £75 by the Games Committee, and the rest from Old Westminsters, Masters and other interested parties. The clock was presented by Old Westminster members of parliament and Llewellyn Atherley-Jones, the radical liberal QC and MP, whose sons attended the school.

The building was formally unveiled at the match between the School and the Lords and Commons, on May 14th 1898.

Despite its attractiveness and location in the heart of an increasingly bourgeois Westminster, the pavilion has not led a charmed life, having seen at least one more ‘grand opening’ before the one in 2023.

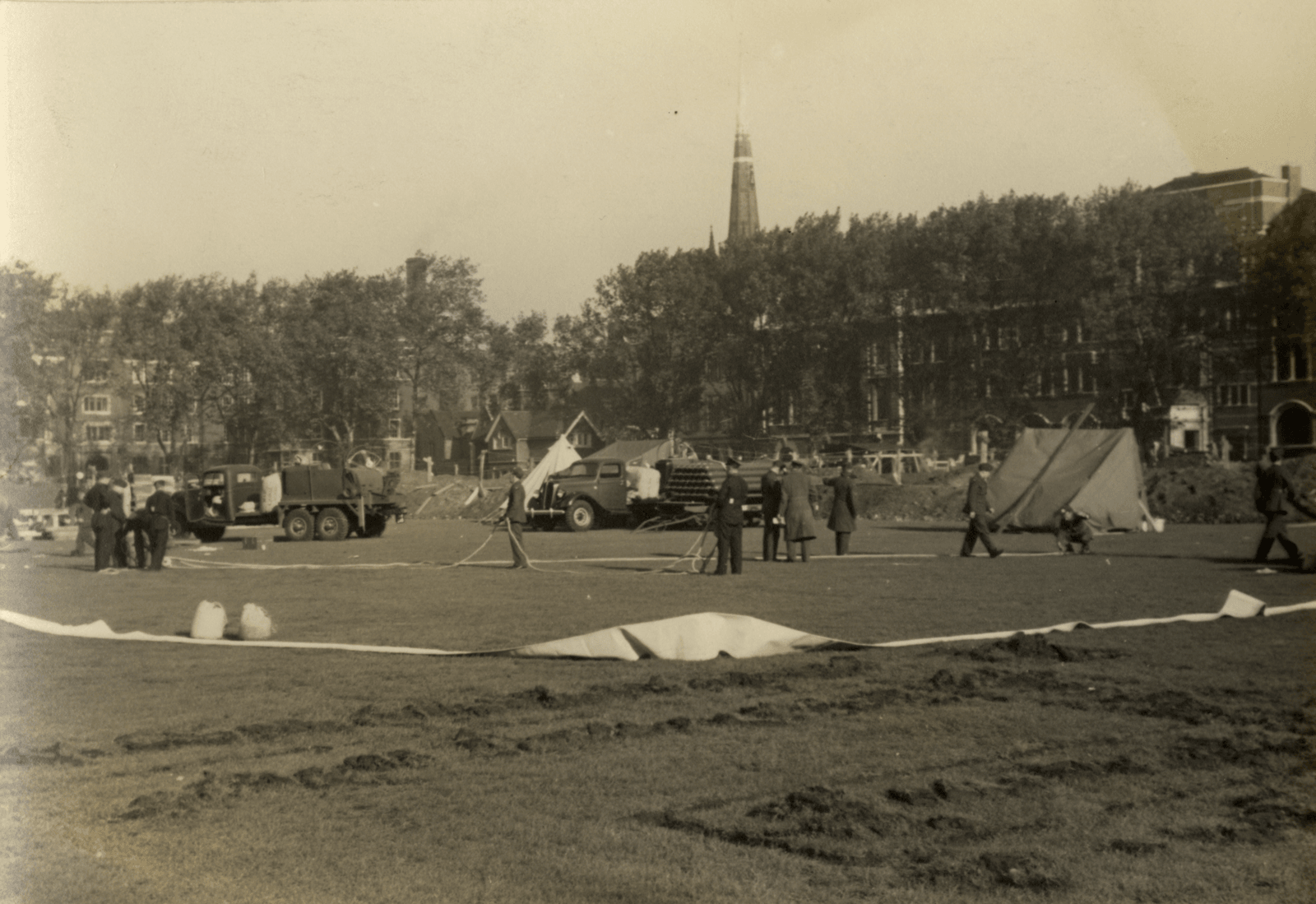

Concerns that gripped the nation at the time of the Munich Crisis in the 1930s led to the requisitioning of Vincent Square by government, which instructed the digging of shelter trenches along the east and south sides of Vincent Square, with a concrete barrage balloon base constructed in the centre. After the War the site was abandoned. Railings had been removed for scrap iron and the area was littered with the residues of war: shelters, static water tanks, American army trucks and barrage balloon anchorages. It was noted as being a ‘battleground for local children’. The pavilion was partially wrecked.

Post-War rebuilding was a major, and slow, operation. For three peacetime years there was no sport at Vincent Square.

Competition only resumed in June 1948, with the pavilion reopened by distinguished guests including Ashes winning captain and MCC president Sir Pelham ‘Plum’ Warner.

75 years on, the pavilion enters its next phase of life. Gone is a single-storey 1930s extension on one side of the wood-framed main building, and added are two new extensions to either side, with tent-like roofs designed by Ptolomy Dean, surveyor to the fabric of Westminster Abbey, and inspired by John Nash’s grade II*-listed Rotunda at Woolwich Common.

Related News Stories